Steinholt

In 1929 my wife’s paternal grandparents came to the fishing village of Þórshöfn in north-east Iceland from outlying crofts. They built a small house by the sea and named it “Steinholt”. Unforeseen events led us to acquire the house in 2010, since when it has become the base for a photographic study or the area. My itinerary retraces the movements of my wife’s forefathers, as they crisscrossed the region from farm to farm in search of work or a place to live. Their lives undoubtedly mirrored many who strived for existence during difficult times. Set against the rugged beauty of a remote and unheralded region of Iceland , the aim of this project is to remember their endeavour and determination, and since the past always resurfaces on in one form or another, I see more clearly the woman with whom I have shared my life for over 30 years.

Álfheiður and her nafna.

In 2009 my wife Álfheiður returned to Þórshöfn, her father’s village, situated at the base of the Langanes peninsular in the far north-east corner of Iceland. She had intended to repair the cross that marks the place where her grandmother is buried, in the nearby cemetery at Sauðanes. As a child, she travelled to Þórshöfn each summer from Reykjavik, to stay with her grandparents. Those months spent in the company of her grandmother, after whom she is named (nafna – named after), are among her happiest childhood memories.

In 1929, her grandparents Álfheiður Vigfusdottir and Sigfus Helgasson built Steinholt, a small house by the sea close to the harbour in Þórshöfn. Originally from outlying crofts, for just one year they had been farmers at Flautafell in Þistilfjörður (perhaps in order to be permitted to marry). They brought with them a cow which was housed nearby. The cowshed served as shelter while the house was built, and was where Haraldur, my father-in-law, was born. Sigfus died 7 years later following an outbreak of measles, and Álfheiður remarried in 1942 Johann Kristjànsson, a fisherman. That same year Haraldur left home, aged 14, to eventually pursue a life at sea. Thirty years since her death, Álfheiður is still respected in the village as the unpaid unofficial midwife and doctor’s assistant, and for her readiness to help others despite her own difficulties. For my wife, she was a guiding light of moral strength.

Álfheiður arrived at the cemetery situated on a rise overlooking the fjörd on an overcast day of drizzle. An unexpected parting of the clouds briefly bathed the hill in sunlight which she took for a sign. The following day she decided to revisit her grandmother’s old house. The owner, an elderly bachelor named Agnar, happy to see a visitor, invited her in for coffee. Few are forgotten in remote communities, and Agnar remembered my wife as a child playing in front of her grandmother’s kitchen. Closing her eyes Álfheiður could imagine the kitchen as it had been 40 years before – the smell, a mixture of coffee, dried fish and smoke seemed unchanged.

The visit was not without consequences. While we were visiting family in Iceland the following year, Agnar sent word that he wished to sell us the house at a low price. Tired of living alone, he had found a place at Þórshöfn’s retirement home. Having no immediate family, he wanted Álfheiður’s house to belong to her nafna, so we decided to accept his generous offer.

I am frequently drawn to this house by the fjörd. My attachment to Iceland is closely bound to my feelings for my wife, and the events that have shaped her life. The surrounding land seems inhabited by memory, made more poignant now that I have researched local and family history. Walking alone in this wild and unforgiving landscape such stories evoke the Sagas.

For many years from 1948 Agnar kept a diary. He also hailed from an isolated and now abandoned croft prior to moving to Þórshöfn. Rarely leaving the village, the diary mostly catalogues ever-changing weather patterns. This would seem to have filled his world.

Of my wife’s forefathers, various stories are retold by family. The following are examples. In addition, two detailed accounts were collected and published in 1951 by Benjamin Sigvaldsson, an itinerant teacher and labourer who travelled the north-east during the 1940’s. They are available separately and have been valuable reference material for my project.

Hreinn

Álfheiður Vigfusdottir had a child, named Hreinn, with Johann her second husband. When four years old, the boy caught meningitis and his condition soon deteriorated. It was wintertime, and since the roads were snow-bound, the way to the nearest hospital was by boat. Hreinn did not survive the journey. The distraught couple (Johann lost both his first wife and child in childbirth), without money and unwilling to wait some days for the next boat, made the return journey of some 100 kms from Húsavík on foot with the body of the child on a sledge in order to bury him at Sauðanes where today his parents also lie.

Ólína at Kuða

Ólína Ólafsdóttir and Vigfus Josefsson were my wife’s great grandparents. They were farmers at Grimsstaðir in Þistilfjörður where their daughter Álfheiður was born. Later they moved over the hill to Kuða to join their son Johannes. One spring, after the long dark months of winter, Ólína revealed that she had seen lights resembling lit windows shining from a large rock by a stream.

Olina’s gave an account of her long and difficult life to Benjamin Sigvaldsson, published shortly after in “Sagna paettir”.

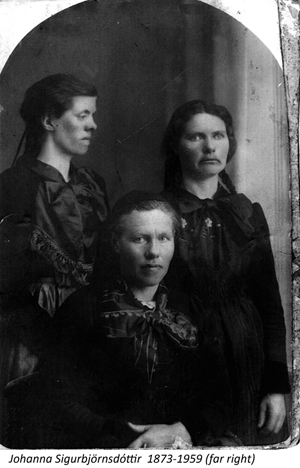

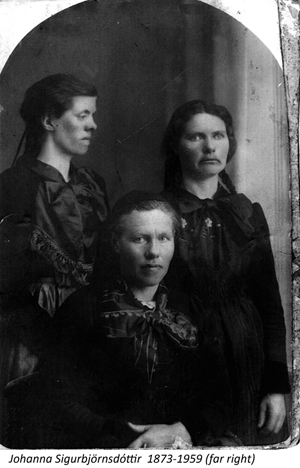

Johanna and Hjalmar

Sigfus, my wife’s grandfather, was born at Harðbakur, at the top of Melrakkasletta, which I have been told is the world’s 10th windiest place. His parents, Helgi Haldorsson and Johanna Sigurbjörnsdóttir, were farmhands who later rented a nearby croft and raised a few sheep. One morning in December, with the land shrouded in darkness, Helgi went in search of an errant sheep. He failed to return and it was after some days that he was found sheltering behind rocks to wait out a snowstorm frozen to death. Johanna was taken by the parish authorities and given to a local landowner to work in exchange for food and shelter. She was raped by the farmer and became pregnant. The farmer would not keep two children and Sigfus, aged 6, was sent to work elsewhere. Johanna gave birth to a son, Hjalmar. The boy was diligent and determined and eventually held land in his own right, taking in his mother to whom he was greatly attached. Later, as a gesture of remembrance to Sigfus his half-brother, Hjalmar bought two chandeliers to decorate the small church at Svalbarð where Sigfus was laid to rest. In this way, he could show that he and his kin could no longer be considered destitute.

Some years later, while in his 70’s, Hjalmar was rounding up sheep at Ytra Áland in Þistilfjörður. He was surprised that he could no longer run like he used to but decided the problem lay with his rubber boots.

Fagranes

Sigfus’ father was Helgi , the son of Halldór Helgasson and Anna Ólafsdóttir who were the first and last to live at Halldórskot, a remote croft which they originally named Fagranes, deep inland in Þistilfjörður where the climate is more extreme. They raised a few sheep, perhaps able to roam the hills, which being in the shadow of mountains, were relatively snow-free in the winter. It is recorded that Anna was a woman of great courage. One day she set out with a horse for trade and provisions from Raufarhöfn – a return journey of 6 days across rugged terrain. She took along her youngest child who she was still breastfeeding. The journey back was made extremely difficult by thick fog, and straining to follow the trail, she discovered after some time that the baby had gone from the basket on the horse’s back. Painstakingly retracing her route for some distance she searched in vain until eventually, on the verge of giving up, the baby was found asleep, alive and well, where he had rolled off into a hollow. Perhaps the baby was Helgi, but we cannot be sure because there were four children at Halldórskot.

Later, when widowed, Anna lived in a small turf hut in Raufarhöfn where her open-door hospitality to numerous passing guests was a cause of bewilderment in the vicinity given her undeniable poverty, and despite the best efforts of the powerful local Factor in the large premises opposite to have the hovel pulled down. Her story is also recounted in detail in “Sagna paettir”.

Heljardalur.

One of the ealiest of my wife’s paternal ancestors that we have traced was also named Halldór (1668-1707). He was the farmer at Skálar, near the end of Langanes, a farm which had been occupied since the settlement. Conditions during the late 18th century were extremely difficult, particularly following the catastrophic eruption of the volcano Laki in 1783 which provoked widespread famine.

It is said that around this time the decision was made at Vopnafjörður to collect together the elderly, the handicapped or infirm, and the destitute, and take them to Heljardalur, a remote valley some 50kms as the crow flies inland from Þórshöfn, to be abandoned shortly before the arrival of winter. There is mention of one young woman who managed to escape this certain death, by demonstrating her aptitude at various skills to a farmer on Þistilfjörður who eventually took her in.

The Mountain.

The image of the mountain changes and the mountain acquires a name. The name gives the mountain a definite history, the history of the knowable. The history of those who know the mountain and therefore gave it a name.

In the age of the knowable, when everything has been given its name, it is difficult to find nameless mountains. The mountain does not insist on a name; rather, man insists on his name for the mountain.

Thus he creates the history of that which is reflected in his own knowledge.

With that knowledge to rely upon, man conquers nameless mountains.

Birgir Andrésson 1955-2007 (artist, friend and Álfheiður’s cousin), 1994